Intermittent Space: Sound, Violence, Ambiance and Affective Politics of Fear in Contemporary Mexico.

by LUZ MARÍA SÁNCHEZ CARDONA

- View Luz María Sánchez's Biography

Luz María Sánchez is a transdisciplinary international artist and researcher based in Mexico City. Sánchez is a Professor at Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana.

Intermittent Space: Sound, Violence, Ambiance and Affective Politics of Fear in Contemporary Mexico.

By Luz María Sánchez Cardona

1

Lucciole are minor sparks, like fireflies that subsist in the context of a ferocious, strong, permanent light. Following Pier Paolo Pasolini, Georges Didi- Huberman links the possibility of the survival of these lucciole to the existence of an interstitial and intermittent space - that is, in opposition to a totalitarian machine. Didi-Huberman takes this image from Pasolini’s 1977 ‘L’articolo delle lucciole’ [“The fireflies’ article”], in which Pasolini describes Italy’s political situation in the late 1970s through this fireflies metaphor:

It consists of a funeral on the moment, in Italy, of the disappearance of fireflies, those human signals of innocence annihilated by the night - or by the “fierce” brilliance of the spotlights - of triumphant fascism. (Pasolini qtd* Didi-Huberman 18)

During the first six years of the so-called Mexican Narco War [2006-2012], former President Felipe Calderón liked to appear in a military uniform as Mexico’s Drug War Commander in Chief. The main target of his military strategy was to reclaim the control of the states where Mexican cartels were in charge. Thus, Mexico’s Drug War began as a decision to recover sovereignty in the context of a political and social crisis. At the end of this period, there were more than 45,000 military personnel deployed - in the states of Mexico, Baja California, Tamaulipas, Michoacán, Sinaloa and Durango - and more than 60,000 casualties. By the end of President Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration [2012-2018], there were more than 40,000 disappeared civilians and more than 150,000 casualties. At present, during Andrés Manuel López Obrador presidency, the numbers are around 250,000 casualties and more than 73,000 disappeared civilians (Lastiri, 2020), as well as an incalculable number of displaced individuals (Volpi).

I find direct parallels between Pasolini’s idea about the advent of a new fascism back in 1975 and contemporary Mexico. According to Didi-Huberman, Pasolini describes the scenario in two moments:

[Phase 1]

marked by “police violence and disregard for the constitution,” all of it drenched in “atrocious, stupid and repressive State of conformity,” against which “intellectuals and opposition of this period cherished ridiculous illusions” of political reversal.

[Phase 2]

began, according to Pasolini, at the very moment that “the most advanced and critical intellectuals did not realize that ‘the fireflies were disappearing’ (Didi-Huberman 19-20.

The scenario which contemporary Mexico is embedded-in, responds to those phases proposed by Pasolini.

2

I have been an observer - approaching women and men on their hunt for their lost ones, victims of forced disappearance. Listening to their laughter, and then, in the studio, listening to the details of their private lives1, I could hear scarcity, depression, illness, loneliness, even under-nourishment. I sensed the individual glow of each one of the participants, fading away.

The corruption of the structures of the Mexican State places these individuals in a situation of permanent vulnerability and fragility. Nevertheless, they shine. They know the instruments and procedures of the killing machine. This double-headed structure, on one side the ‘power machine’ (Agamben) and on the other, the ‘war machine’ (Mbembe). They have seen their faces. They know that they are ruthless: both the Government/State and its legal apparatus of violence - police and military forces - and the irregular armies that make up cartels. Nobody can claim a monopoly on violence anymore. Nobody can ‘save’ the fireflies. Yet, they endure, and - no matter what - they shine.

The incubation, growth, and [re]surfacing of these minuscule single-glowing individuals, in a context of general despair, has been driving my explorations since I moved back to Mexico in 2007. My practice has been circulating in and around these interstitial and intermittent spaces, looking for those “openings, of possibilities, of flashes, in spite of all” (Didi-Huberman 29). I want to understand, first hand, how these individuals endure.

3

Summarizing the current situation in Mexico as territory I should say that the narrative of Narco War2 that we have been told again and again - a war with no sides, with no clear objective, where the only ones losing everything are civilians - is contributing to diminishing the real depth of the horror. What is in place is war “made up of segments of armed men that split up or merge with one another depending on the tasks to be carried out and the circumstances.” For Achille Mbembe, war machines “are characterized by their capacity for metamorphosis” (Mbembe 32) and a mobile relation to space. And something that makes sense in the Mexican scenario, is that “[T]he state may, of its own doing, transform itself into a war machine (Mbembe 32). In Mexico, this war machine is dismantling all safety-nets: the collusion of police, the corruption of the military forces, the obvious participation of politicians and members of the government makes it almost impossible for civilians to understand and trust their surroundings.

When describing the state of exception as a practice of contemporary states “including so-called democratic ones,” (Agamben/B 2) Giorgio Agamben is clear:

modern totalitarianism can be defined as the establishment, by means of the state of exception, of a legal civil war that allows for the physical elimination not only of political adversaries but of entire categories of citizens who for some reason cannot be integrated into the political system. (Agamben/B 2)

Mbembe’s term necropower also comes to mind here, since it is a “concatenation of biopower, the state of exception, and the state of siege” (Mbembe 22). But above all, there is an absence of the State in the Mexican reality; necropolitics at its best, as defined by Mbembe, are “contemporary forms of subjugation of life to the power of death” (Mbembe 39). For Agamben, the anthropological-machine uses “of power, violence and the state of exception (Benjamin, Schmitt) is still at the basis of modern and contemporary democracies” (Bartoloni 103). When I said that civilians in Mexico have seen this killing machine, the concept I am referring to synthetises the concepts power machine and anthropological-machine (Agamben) plus war machine (Mbembe). All of these concepts are useful when trying to understand Mexico as malleable territory, where the ambiance of distressful sonic ecologies pervades - a sonic space of fear.

4

Fear. In Mexico - the symbolic and real territory that I have been exploring for the last 18 years - what we see is the result of a wide-range of decomposition of all circles of coexistence. This is evident when we address another side of this problematic: the lack of empathy between fellow citizens, which may only come from fear. As Sara Ahmed states:

the relationship between fear and the alignment of bodily and social space, in particular [by considering] how fear shrinks bodily space and how this shrinkage involves the restriction of bodily mobility in social space. (Ahmed 64)

This is fear of having the same fate as those people that we see as detached and far away from us. This is “fear as an ‘affective politics’, which ‘preserves’ only through announcing a threat to life itself” (Ahmed 64). Silence among communities is the norm under such fear. Individuals find themselves alone, in the strictest sense, not even the police will come to help. Fear is, then, a way of control:

[R]ather than fear being a tool or a symptom, I want to suggest that the language of fear involves the intensification of ‘threats’, which works to create a distinction between those who are ‘under threat’ and those who threaten. Fear is an effect of this process, rather than its origin. (Ahmed 72)

This control takes place in a space. The social space, the private space, a sonic space of fear. People close off and quit the social space because of fear. And they lock themselves in because of fear.

[F]ear works to align bodily and social space: it works to enable some bodies to inhabit and move in public space through restricting the mobility of other bodies to spaces that are enclosed or contained. It is the regulation of bodies in space through the uneven distribution of fear which allows spaces to become territories, claimed as rights by some bodies and not others. (Ahmed 70)

Social scrutiny and revictimization does the rest. And again, the question persists: how do lucciole survive?

5

I see my art research practice as an open field. In this arena, I located myself within my areas of expertise, from where I can explore other angles that I consider essential within the art research project, in this case V.[u]nf. In addition I define my art research practice as political in the Agambeian sense of what politics and art are, since both designate “the dimension in which linguistic and bodily, material and immaterial, biological and social operations are deactivated and contemplated as such” (Agamben/A 43). And if, as stated by Jacques Attali, “Eavesdropping, censorship, recording, and surveillance are weapons of power. [And] The technology of listening in on, ordering, transmitting, and recording noise is the heart of this apparatus” (Attali 7) then the counter-surveillance, the counter-recording, the counter-eavesdropping, the counter-censorship are also weapons of power which I use as part of my art practice. Jordan Lacey states, “there is a direct relationship between noise and power and […] these power relations might be shifted” (Lacey 35) by the art practitioner. In this case, as an art practitioner, I intervene and deactivate social operations through my translating aesthetic constructs.

6

Vis. [un]necessary force. The Sound of Post-National Mexico is a research-creation project that explores contemporary violence in Mexico and its derivations in the daily life of civilians. Its title originates from the Latin root Vis: “Force. Virility. || Virtue, property. || Violence, arrogance. || Authority, credit, power” (Salvá 907). The prevailing discourse, from the Mexican State and from criminal groups, indicates that this is a necessary violence. The wager of my project - by including the prefix un - means that the possibility of another world is possible.

For groups within this war machine it is essential to send communications, mark territories and terrorize populations through their enemies’ bodies. Michel Foucault addressed the topic of modern punishment in panopticon spaces where the body was isolated in hygienic spaces, in opposition to the pre-modern “tortured, butchered, amputated” body “exposed dead or alive, offered in spectacle”3 (Foucault 10). In Mexico, there is a resurgence of this butchered-tortured-exposed body. Ileana Dieguez introduces the concept of the exercise of fear and affirms that:

The scenes of violence reach their highest point in the bodies, crossed by power relations. The bodies of violence will always be irreversibly dislocated bodies. The images produced in these circumstances constitute the most powerful emblem for the exercise of fear. (Dieguez 4)

In Mexico what we see is a reiteration of this annihilated body, of this body that has been tortured through the exercise of fear. V.[u]nf stands on the ground that the situation of extreme violence inflicted on civilian groups is unnecessary. Why use extreme violence on corpses that will later be dissolved in acid or cremated in a ditch? We face the killing machine.

7

Through this project, I have sought to encourage the participation and interaction of individuals living in a state of exception: the lucciole. The main question that drives the project is: How does the civilian population in Mexico live through extreme violence in a State that has revealed its own failure? The problem is complex and despite the change of administrations and political parties in Mexico from 2006 to 2020, things remain the same. However,

there is no official data one could relate to, there is continuous intimidation of media and journalists; there is lack of trust in the state representatives - from mayors and judges, to street police. Could it be that the state itself - from its edges to its centre - is suffering from a process of permanent decomposition, which makes it impossible to navigate reality armed with the lingua of 21st Century democracies. (Sánchez Cardona 255)

As Ana María Ochoa Gautier clearly indicates there are “different ways of forced silence” (Ochoa Gautier); and in Mexico silencing is part of the politics of fear. In fact, “[T]he simple act of sharing an experience, by way of trust - if the wrong listener is on the other side - may bring direct physical violence to the person voicing reality. Entire communities are living in a state of despair, fragility, and even terror” (Sánchez Cardona 256). Silencing communities pervades as a tool of control – propagating a fearful ambiance.

8

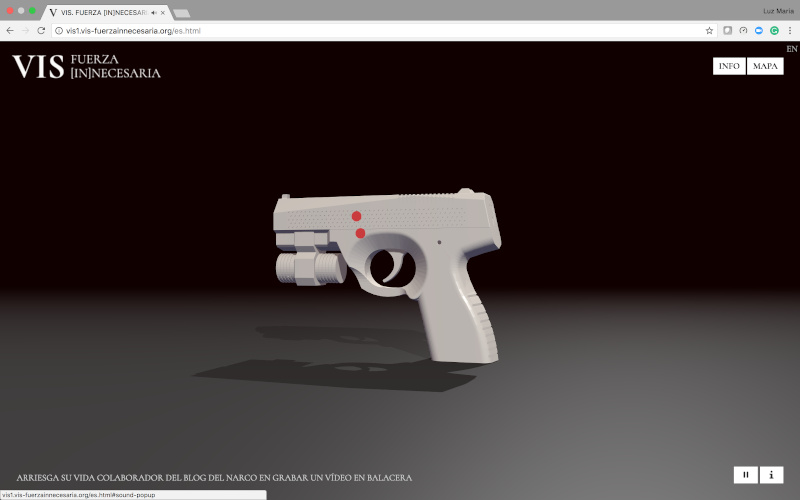

V.[u]nf_1 (2014-2015) and V.[u]nf_1.01 (2017-to present) are the first of the four artworks in this series. These are multimedia, asynchronous, participatory and interactive installations. They are comprised of sculptural objects, texts/data, a map, sound files, and a parallel piece that operates on the internet.

The sculptural objects are digital audio reproducers in the form of a Caracal F 9x19 mm pistol, and each of them contains the recording of a shooting.

The audios originate from video recordings made by citizens with their own mobile phones that afterwards they put into circulation through the YouTube platform. When visitors arrive at the exhibition space, they find the sound devices, the map, the information related to the origin of the recordings – but the space is silent; that is, there is no device turned-on.

The installation has a participatory character in two crucial dimensions: in the production, because the audio data had been generated by numerous, specific persons, who this way contributed to the creation of the work; and in the dimension of the audience’s experience, because they determine how they want to use the installation – by pressing a button designed for that purpose, they may (or may not) play the sounds off of the gun-sculptures and listen to the shooting. (Kluszczynski 42)

V.[u]nf_1.01. ZKM, Karlsruhe. 2017. Photo credit Ina Čiumakova.

The online version, V.[u]nf_1.01,operates similarly: we are presented with a single model of the pistol-shaped sound device, and through a series of red dots, the user activates the sound files.

V.[u]nf_1.01, website version. Courtesy of the artist.

If one of these devices is activated we listen to a micro-landscape, a snapshot. But the visitor can activate as many devices as they wish in the order they consider appropriate: then the roar of the war in which civilians are immersed in Mexico takes place.

V.[u]nf_1. Studio documentation, Mexico City, 2015. Photo credit Cecilia Hurtado.

This roar is made of fearful ambiances, captured via mobile phone recordings, that, when translated into the exhibition space-based devices, become a new medium. The audience gains a control over this roar that could never be achieved in the original environment.

V.[u]nf_1.01. ZKM, Karlsruhe. 2017. Photo credit Ina Čiumakova.

When the first version of the multimedia installation V.[u]nf_1 was inaugurated in the northern city of Matamoros4 – in an opening delayed because there was a shooting downtown that blocked all city traffic – I found that the locals, were eager to listen to sound recordings #42, #44, and #45, there was a line of people waiting to operate those gun-shaped sound devices – those where the recordings of shootings from the city of Matamoros. When I asked them why there was such a special interest in those recordings, it was clear to me that there was some sort of validation of their everyday horrors, by having them not in their regular urban soundscape, but within the exhibition space. They found some sort of control over their everyday ambiance of fear, once it was translated to the Tamaulipas Museum of Contemporary Art.

Track #42

Original title: Balacera en Matamoros 17 de noviembre de 20145.

[Shooting in Matamoros November 17, 2014.]

Duration: 0:18 seconds.

Views: 11,223.

YouTube user: ValorporTamaulipas.

Extra information: Published November 17, 2014.

http://www.valorportamaulipas.net.

URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6R3YUt7OHx8

Last reviewed: January 14, 2015. [Active link as for July 20, 2020.]

Track #44

Original title: audio de la balacera matamoros 16 de junio 2011. [sound of the shooting in matamoros june 16, 2011.]

Duration: 11:09 minutes.

Views: 104,067.

YouTube user: chelitogallery. URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U7EQzTRFd_s

Extra information: Updated June 16, 2011. See the videos that I uploaded from the balaceras that I had to be present in Matamoros Tamaulipas

URL: www.youtube.com/watch?v=U7EQz

Last reviewed: January 14, 2015. [Active link as for July 20, 2020.]

Track #45

Original title: Balacera en Matamoros, Tam 16-Junio-2011. [Shooting in Matamoros, Tam June 16, 2011.]

Duration: 15:06 minutes.

Views: 27,130.

YouTube user: 19babyboop.

URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aAvL-Pg75Hg

Last reviewed: January 14, 2015. [Active link as for July 20, 2020.]

While V.[u]nf_1 consists of 74 plastic 9mm Caracal pistol-shaped sound players, V.[u]nf_1.01 consists of 100 sculptural objects made with the additive sculpture method [3D], in a white polymer with integrated sound devices.

V.[u]nf_1, plastic model. Courtesy of the artist.

V.[u]nf_1, plastic model. Courtesy of the artist.

V.[u]nf_1.01, model for additive sculpture (3D) in white polymer. Courtesy of the artist.

These objects are a copy - in the case of V.[u]nf_1 - and a copy of a copy - in the case of V.[u]nf_1.01 - of the 9mm pistol designed by Wilhelm Bubits that is produced in the United Arab Emirates.

9

In his book Sonic Warfare, Steve Goodman reminds us about the “deployments of sound and their impacts on the way populations feel - not just their individualized, subjective, personal emotions, but more their collective moods or affects” (Goodman xiv). When listening to V.[u]nf_1 and V.[u]nf_1.01 we are confronted with 74-100 fragments of a larger landscape, taken from different parts of Mexico as sonic territory. Here are straightforward descriptions of some of them:

Audio: Two men talk in the early hours of the day, trying to guess, by sound, what type of weapon is involved in the shooting and therefore which criminal group, or military or police forces, are involved.

Track #22

Original title: Balacera en vivo Nuevo Laredo Tamaulipas 22082014 Zetas vs Gates. [Live shooting Nuevo Laredo Tamaulipas 22082014 Zetas vs Gates.]

Duration: 1:44 minutes.

Views: 24,510.

YouTube User: Tacos Frios.

URL6: www.youtube.com/watch?v=OAQ636J3ehw

Extra information: Published November 7, 2014.

Last reviewed: January 3, 2015. [Link not active.]

Audio: A young man is trying to imitate the rhythm and sound of gunshots. Tata tatatata tatatatata tatatat tata.

Track #33

Original title: Balacera en Agua Prieta: 2014-2015. [Shooting in Agua Prieta: 2014-2015.]

Duration: 7:51 minutes.

Views: 1,463.

YouTube User: Verde Rap.

URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V2oAWbjnB38 Last reviewed: January 14, 2015. [Active link as for July 20, 2020.]

Audio: A man makes a phone call warning a friend not to go near the house since a shootout is taking place on the corner.

Track #10

Original title: Balacera en Changuitiro Michoacan. [Shooting in Changuitiro Michoacan.]

Duration: 1:39 minutes.

Views: 5,651.

YouTube User: Roberto Deejaysietecerosiete.

URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wsZ5OMHaxxw

Last reviewed: October 20, 2014. [Active link as for July 20, 2020.]

Audio: A woman in the classroom sings with young pre-schoolers about the chocolate drops falling from the sky, to keep the children at floor level during a shooting outside of school.

Track #67

Original title: maestra tranquiliza niños durante balacera en Monterrey mp4 [teacher calms children during shooting in Monterrey mp4].

Duration: 1:20 minutes.

Views: 479,101.

YouTube User: Aristides Lean Nah.

URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AlmNj5T_Brc

Extra information: Updated May 27, 2011. Sometimes we complain about some pseudo teachers who mistreat children, but it is also good to know that there are teachers like this who really know how to deal with difficult situations, congratulations to those great teachers.

Last reviewed: February 17, 2015. [Active link as for July 20, 2020.]

Audio: The sound of a heavy crossfire, with different calibre guns. We can hear the freeway on the distance [traffic], and birds singing at dawn. No sonic presence from the person that did the recording.

Track #3

Original title: Intensa balacera en Zumpango a las 7 de la mañana [Intense shooting in Zumpango at 7 am]

Duration: 3:58 minutes.

Views: 24,463.

YouTube User: solo chilpo.

URL7: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QdovmjQvJzM

Extra information: Published June 29, 2014. www.solochilpo.com. Shooting that was unleashed in Zumpango, started at the municipal police headquarters and extended to the road where two people died on June 28, 2014 at 7AM in the municipal seat of Eduardo Neri, Guerrero. Video sent by Carlos Gerardo Garcia Alvarez.

Last reviewed: October 20, 2014. [Link not active.]

Audio:A birthday party. Kids saying that all of them want cake. They start singing “Feliz cumpleaños a ti” [Happy Birthday to you] when the shooting starts. Cries of children and adults.

Track #8

Original title: Balacera en vivo en fiesta de cumpleaños infantil en Mexico INCREDIBLE [Live shooting at children’s birthday party in Mexico INCREDIBLE]

Duration: 1:19 minutes.

Views: 32,044.

YouTube User: liadiz1.

URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3lxIjBDqxKc

Extra information: Published July 28, 2014. At 8 o’clock on the nigh of July 17, in the middle of the birthday celebration of one of the children, shots were fired which, in addition to leaving him an orphan, injured other people who were at the party, this happened in Mexico where despite the fact that his government preaches that everything is going well, danger and crime is an everyday thing, the full story can be read here: http://www.24-horas.mx/ataque-a-familia- is-not-an-isolated-video-case /

Last reviewed: October 20, 2014. [Active link as for July 20, 2020.]

10

Listening to V.[u]nf_1 and V.[u]nf_1.01 can also be done through forensic listening, a practice that

has the power to discern what of the vast and heterogeneous frequencies of the sonic world can be legally meaningful” (Abu Hamdan/A 204). If we listen attentively, forensic listening will provide “a large amount of information to its production and its form, space in which it was recorded, the machine it was recorded on, the geographical origin of the accent, as well as the age, health and ethnicity of the voice. (Abu Hamdan/B 10mm41ss – 10mm58ss)

In V.[u]nf_1 and V.[u]nf_1.01 we are confronted with recordings made by the people directly involved in extremely violent situations. They were there, on the spot, and had the nerve to take out their cell phones and begin registering the situation. “[S]ound is often understood as generally having a privileged role in the production and modulation of fear, activating instinctive responses, triggering an evolutionary functional nervousness” (Goodman 65). Some of the shooting recordings were made from afar and some from a first range position. But all of them have the sound of the gunshots as a reminder of a nearby extremely dangerous situation, which calls for silence, immobility, restraint: for fear.

People that witnessed these situations did not call the police. They were not indifferent to violence, instead, they decided to become witnesses and to provide testimony through their recordings - in some sort “civil journalism, collecting and sharing information about acts of violence” (Kluszczynski 43-44). Through the videos, we see a segment of what took place: a partial view of a street, the scene below a desk, a recording behind a car door. Instead, through the sound recordings, we listen to elements that may speak of a space and situation without the constrictions of the eye. When approaching V.[u]nf_1 and V.[u]nf_1.01 through the practice of forensic listening we may learn the type of guns used, the time of the day, if it is an indoor or outdoor recording, how many individuals were in the space. Forensic listening is especially useful when approaching the recordings #27 and #29, that took place on the night of 26-27 September 2014, when 43 students were kidnapped and killed in the city of Ayotzinapa8.

Track #27

Original title: Balacera en Iguala (26-27/9/2014); policías y comando matan a 8. [Shooting in Iguala (26-27 / 9/2014); police and commando kill 8.]

Duration: 1:23 minutes.

Views: 26,262.

YouTube user: Anonimo.

URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zkRyS5ZxEdg

Extra information: Published September 27, 2014. Recording from a Facebook user shows the audio of the shooting attack by policemen from Iguala, Guerrero, and a Guerreros Unidos command against Ayotzinapa students, a soccer team, journalists and common people from the city of Iguala, leaving as a balance until the moment 8 dead. Ángel Aguirre Rivero, José Luis embraces Velázquez, what do they have to say? Shooting Iguala, Guerrero, September 26 and 27, 2014.

Last reviewed: January 10, 2015. [Active link as for July 20, 2020.]

Track #29

Original title: balacera en iguala guerrero. [Shooting in iguala guerrero.]

Duration: 0:51 seconds.

Views: 15,748.

YouTube User: MonVel.

URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrWdLH8–Fk

Extra information: Published September 27, 2014. Shooting this Saturday morning, there is little information on the facts!

Last reviewed: January 13, 2015. [Active link as for July 20, 2020.]

This case still stirs Mexico’s public opinion and, even if it remains “unresolved”, gave visibility to the thousands of victims of forced disappearance in the country.

#27, screenshot of original video.

Recording #27, 1:23 minutes, we listen to the voice of a young male, gunshots, and birds:

[Gunshots]

Young male: “Oi, la balacera.” [Listen, the shooting.]

[Gunshots]

Young male: “Se oye super cerca.” [It sounds quite close.]

[Gunshots]

Young male: “Ay Dios mio.” [Oh Lord.]

[Gunshots stop]

[Sounds of wind, dogs, birds.] Young male: [Whispers] [Sounds of wind, dogs, birds.] Young male: “Ya no.” [No more.]

[Sounds of wind, dogs, birds.]

#29, screenshot of original video.

Recording #29, 51 seconds, we can hear gunshots, an older woman, a man, probably a younger man all within an enclosed space, and accordion music.

[Gunshots]

[Cellphone rings (music ringtone)]

[Close to phone] Young male: “haste para allá” [move away]

Older woman: [Answers the phone] “Bueno, ey, ¿otra vez?” [Hallo, yes. Again?]

[Gunshots]

Young male: “¿Qué cosa?” [What?]

[Gunshots]

Older woman: “¿Por todos lados? Ay Dios mío. ¿Ustedes no pueden salir, verdad? No, esténse pues boca abajo, hijo. Sí sí sí, hijo, sí sí sí, ya oí.”

[Everywhere? Oh my God. You can’t go out, right? No, lie on your stomach, son. Yes yes yes, son, yes yes yes, I already heard.]

Older woman and man almost at unison: “Manténganse boca abajo, por favor.” [Stay facing down, please.]

[Gunshots]

Older woman: “Sí hijo, córrele pues, y voy.” [Yes son, run, and I will go.]

[Gunshots]

Older man: “Puta madre.” [Fuck.]

Older woman: “Quiero ponerme a chillar, con la balacera” [I want to cry, with this soothing.]

Older man: “¡Cálmate, ya!” [Calm yourself, now!]

[Background accordion music]

By approaching these real events through their sound components and coming to terms with their highly political power, we understand better the world in which they participate (Abu Hamdan/B 11mm00ss- 11mm14ss). Each of the recordings of V.[u]nf_1 and V.[u]nf_1.01 were meant to be seen/heard since, as I mentioned above, they were videos made with a cellphone and uploaded to YouTube. These recordings could be used, through the forensic approach, as part of a process of justice. Even if the political process that is taking place in Mexico does not assure access to justice at the present, it is important to start building awareness and empathy as a starting point, to eventually move to a forensic-justice like approach.

However, my primary interest rests in exploring the affective politics of fear found in these recordings, and to translate these fearful ambiances into the exhibition space, which brings the audience’s attention to the everyday experience of violence. Since these ambiances of fear are translated into the safe arena of the exhibition space I have decided to provide detailed information about each recording, to make clear to the installation’s visitors the following points:

- These are real recordings of shootings that took place in a city in Mexico.

- These are recordings made by citizens, who are no different to the exhibition visitors

- These situations can occur at any time, in any place, and in any social context.

I am aware of the importance of maintaining a controlled approach to the sonic elements of the artwork in order to avoid dismantling the emotional power of the field recordings, embedded in the participatory affective sonic constructs. These carefully orchestrated steps contribute to the installation’s affective politics, which seeks to translate the feelings of terror across large regions under a state of siege, to a global audience.

11

The direct testimony in each of the recordings included in V.[u]nf_1 and V.[u]nf_1.01 were made while driving in an urban area, before leaving an office, in the vicinity of a kindergarten, in a rural home. They were captured at dawn, at dusk, in the middle of the night, at midday. There are recordings from various cities in Mexico: Apatzingán, Matamoros, Veracruz, Mexico City, Ayotzinapa, Monterrey. In any city, in any circumstance, at any time, the possibility of violence and death.

Screenshot of original video. Sound #10.

Screenshot of original video. Sound #19.

Screenshot of original video. Sound #35.

Screenshot of original video. Sound #60.

The sounds of shootings may be the result of gunmen from different cartels in town, military patrolling nearby, special police trespassing a neighbour’s home. The sounds of shootings become fear, which “projects us from the present into a future. But the feeling of fear presses us into that future as an intense bodily experience in the present” (Ahmed 65). The sonic space of fear from Mexican cities are caught in those short fragments of sound.

Mexico, as a sonic territory, is made of those fragments. By translating the original sonic environment – recorded – to the controlled area of the exhibition space, I am creating a sonic space where an ambiance of fear and a sense of urgency prevails. By including each one of those recordings in sound devices in the shape of a Caracal 9mm pistol and by inviting visitors to activate them and listen, I am again translating the fearful ambiances of Mexico’s affective sonic territory to the exhibition space.

V.[u]nf_1.01. Museum of Modern Art, Mexico City. 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

These multimedia installations can be seen as participatory affective sonic constructs through which we become aware of the nuances of everyday life completely broken by extreme violence.

V.[u]nf_1.01. WRO Biennial, WRO Art Center, Wroclaw. 2019 Courtesy of the artist.

I described in part 8 how visitors behaved within these participatory affective sonic constructs. Having the sounds of their day-to-day lives translated into the exhibition space offers them temporary control over the fearful ambiances with which they are forced to live. This occurs in two ways: by being able to manipulate [on/off] the Caracal-pistol shaped sound devices; and by discovering they are one amongst many citizens living with this reality. The political force of sound through the multi-layered elements of V.[u]nf_1 and V.[u]nf_1.01 invites visitors to feel and eventually to understand the unavoidableness of the killing machine.

12

V.[u]nf_1 and V.[u]nf_1.01 introduces Mexico as a state of exception trough sound recordings made by citizens under the siege of the killing machine. We may listen to these snapshots from an anthropological or a forensic standing point: the fact is that this is a space of fear in which the ambiance of distressful sonic ecologies pervades. This affective sonic territory is carefully translated to the exhibition space into participatory affective sonic constructs, for larger groups of individuals to experience the sonic politics of fear installed within the territory. Since I propose to ponder on how defenceless individuals, compelling lucciole, endure - scintillate - in a space where the killing machine has contaminated all circles of coexistence, these participatory affective sonic constructs may help build empathy, knowledge, spaces of shared experiences, and eventually will contribute to build a path to justice.

Works Cited

Abu Hamdan, Laurence/A. “Forensic Listening.” Audio Culture, Revised Edition, Readings in Modern Music, edited by Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner, Bloomsbury, London, 2017, pp. 199-206.

Abu Hamdan, Lawrence/B. “Video of my Keynote Lecture @ What Now? The Politics of Listening”. Art in General at the New School, June 12, 2015, last retrieved 17 July, 2020.

Agamben, Giorgio/A. Creation and Anarchy. The Work of Art and the Religion of Capitalism, translated by Adam Kotsko, Sandford, Stanford University Press, 2019.

Agamben, Giorgio/B. State of Exception, translated by Kevin Attell, University of Chicago, Chicago and London, 2005.

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2004.

Attali, Jacques. Noise. The Political Economy of Music, translated by Brian Massumi, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis/London, 2002.

Bartoloni, Paolo. “Indistinction.” The Agamben Dictionary, edited by Alex Murray and Jessica Whyte, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2011, pp. 102-104.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Survival of the Fireflies, translated by Lia Swope Mitchell, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, London, 2018.

Dieguez, Ileana. “Los cuerpos de la violencia y su representación en el arte”. Cena 14: 1-12, 2013.

Foucault, Michel. Vigilar y Castigar. Nacimiento de la prisión, Buenos Aires, Siglo veintiuno editores, 2002.

Goodman, Steve. Sonic Warfare. Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear. Cambridge (Mass) and London, The MIT Press, 2010.

Kluszczynski, Ryszard W. “From the Collection of Personal Memories to Collective Memory. Notes on the Archiving Trend in New Media Art”. Czas Kultury [Time of Culture], 2019, No 2, pp. 38-39 42, 43-44.

Lacey, Jordan. Sonic Rupture. A practice-led Approach to Urban Soundscape Design. London and New York, Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Lastiri, Diana. “En México hay más de 73 mil personas desaparecidas: Segob”. El Universal. July 13, 2020, retrieved from: eluniversal.com , last reviewed July 4, 2020.

Mbembe, Achille. “Necropolitics.” Translated by Libby Meintjes, Public Culture 15(1): 11-40. Duke University Press, 2003.

Ochoa Gautier, Ana María. ‘Artes, cultura, violencia: las políticas de supervivencia’. Proceedings from the Conference Culture and Peace: Violence, Politics, and Representation in the Americas, March 24, 2003, 25).http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/etext/llilas/cpa/spring03/culturaypaz/ochoa.pdf, last retrieved September 12, 2016.

Pasolini, Pier Paolo. “L’articulo delle lucciole.” Saggi sulla politica e sulla società, edited by W. Siti and S. De Laude, Milan, Arnoldo Mondadori, 1999, pp. 4040-11; also in Scritti, Milan, Garzanti, 1977. “Disappearance of the Fireflies.” Diagonal Thoughts, edited by Stoffel Debuysere translated by Christopher Mott, Crussels, June 12, 2014. Last retrieved July 20, 2020.

Raphael, Ricardo. “El México de AMLO aún padece los síntomas de un narco-Estado” The Washington Post, August 11, 2020, retrieved from: , last reviewed: August 11, 2020.

Salvá, Vicente. Diccionario Latino-Español, Valencia, Librería de Mallen, 1846, p. 907.

Sánchez Cardona, Luz María. “Vis. [un]necessary force. A socially engaged creative practice research project.” ISEA2017 Manizales BIO-CREATION AND PEACE. Proceedings of the 23rd International Symposium on Electronic Arts, edited by Julián Jaramillo and Andrés Burbano, Bogota, Departamento de Diseño Visual, Universidad de Caldas e ISEA International, 2017, pp. 255, 256.

Volpi, Jorge. ‘El peor lugar.’ Reforma. May 18, 2019, retrieved from: https://busquedas.gruporeforma.com/reforma/BusquedasComs.aspx, last reviewed: May 20 2019.

Footnotes

- I was listening to the sound recordings when making the immersive artwork Vis. [un]necessary force_4 I was working on in February 2019. These private testimonies I did not use.↩︎

- The official discourse is that this is a war against drug cartels; thus, they call it a narco war. Just recently President of Mexico Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) stated that Calderón’s Presidency was a Narco-State (Raphael) in an attempt to distance himself and his government from it. Instead, this drug war is part of necropolitics’ dynamics, in which the Mexican government – including the one AMLO represents – have been taking part.↩︎

- Translations by the author when not indicated otherwise.↩︎

- Vis. [un]necessary force_1 won the 1st Artist Prize of the Frontiers Biennial, Mexico 2014. Exhibition took place in Spring 2015 in the city of Matamoros, and an exhibition in Mexico City follower.↩︎

- The author respected grammar and typos in ‘titles’ and ‘extra information’ from each YouTube entry in the Spanish version of the piece, and tried to keep same criteria on the translation proposed for this article.↩︎

- Broken link: “Video unavailable. This video is private.”↩︎

- Broken link: “Video unavailable. This video is no longer available because the YouTube account associated with this video has been terminated.”↩︎

- In 2019 the collective Forensic Architecture released a project around this case, titled “The Enforced Disappearance of the Ayotzinapa Studens” which was exhibited at Contemporary Art University Museum (MUAC) in Mexico City. Solo exhibition. Forensic Architecture: Hacia una estética investigativa. Dates: 09.09.2017 - 30.12.2017. Info: https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/the-enforced-disappearance-of-the-ayotzinapa-students. See also: http://www.plataforma-ayotzinapa.org/.↩︎